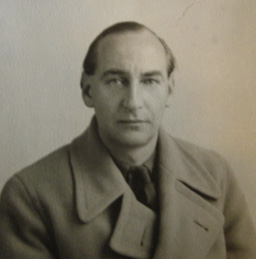

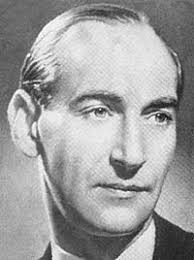

Nigel Marlin Balchin was born on the third of December 1908 in the small Wiltshire village of Potterne, near Devizes. Nigel’s father, William, was born in Godalming, Surrey; his mother, Ada, was originally from Wolverhampton. According to the 1901 census, William was a master baker at the time. Later, the family moved to nearby West Lavington when Nigel won a scholarship to Dauntsey’s School and his father opened a bakery and teashop in the village. Nigel had two siblings: an elder brother called Bill and an elder sister, Monica, who was badly afflicted by arthritis from a relatively early age. Nigel’s scholastic career was extremely impressive: during his time at Dauntsey’s he played hockey, football, rugby and cricket for the school, captaining the school at both football and cricket, won a number of prizes and was made captain of the school in his final year.

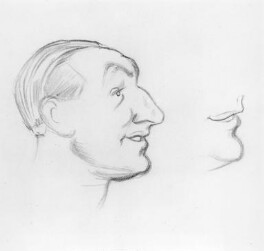

In 1927, Nigel was awarded a scholarship to Cambridge University by the Ministry of Agriculture to study natural sciences and took up his place at Peterhouse College in the autumn of that year. He played rugby, hockey and golf for the college and edited the Peterhouse magazine in his second year. He also sung in the Peterhouse choir, one of his fellow choristers being James Mason, who would go on to be a long-time friend, and of course a very famous actor. Nigel won a prize in his first year, later joking that the examiners must have mistakenly added in the date when they marked his paper. He was awarded a second for natural sciences in Part I of the Tripos in his second year, did not take a Part II in any subject and graduated on 24 June 1930 with a Bachelor of Arts degree with no class attached. In his final year at university he had studied agriculture and psychology.

It was perhaps indicative of Nigel’s ability that when he left Cambridge he was able to secure a position with the National Institute of Industrial Psychology (N.I.I.P.). The N.I.I.P. had been founded in 1921 by a psychologist called Charles Myers; it was a non-profit-making organisation, and its aim was to employ the relatively new technique of psychology in the workplace. As well as improving efficiency and productivity, i.e. helping the employer, the N.I.I.P. also sought to improve the conditions of the worker. The organisation deliberately set its wages higher than those in academia, in order to attract high-calibre graduates. On 18 August 1930 Balchin was taken on as an investigator, with a starting salary of £396 per annum. Although initially seconded to Rowntree’s chocolate factory in York, Nigel also carried out investigations for other firms (such as the cornflour manufacturers Brown & Polson) whilst he was with the N.I.I.P.

Nigel’s association with Rowntree’s would last for almost 25 years. In his early days at York he seems to have been mostly involved in work aimed at improving the environment of the factory workers. Later, he started to have a more direct role in chocolate manufacture. The chocolate assortment Black Magic was one of Balchin’s (and the N.I.I.P.’s) great success stories. Nigel established a panel of chocolate testers and sent them samples for tasting. He employed a psychological approach to market research, which can be summarized as follows: “Give the customers what they want, rather than what the company thinks they ought to have.” As Balchin himself put it: “If our main market consists of intellectually self-conscious, upper-middle-class women, we shall do no good at all with a label representing Stag at Eve or Highland Cattle at Sunset.” The consumer survey established that most chocolates were bought by men to give to women and that such men would prefer a plain, simple-looking box. The Black Magic design remained unchanged for a great many years and, despite a recent modernisation, it still looks much the same in 2008 as it did when Balchin first conceived it in 1933. The types of chocolates inside the box were also determined by Balchin’s customer panel and, for the first time, a chart was included in the box to show which chocolate was which.

In 1933 Balchin married Elisabeth Evelyn Walshe, whom he had met when they were both students at Cambridge. Their first child, Prudence, was born the following year. Also in 1933, Nigel launched his writing career when his first articles appeared in Punch, beginning with a series of pieces entitled ‘The Compleat Modern’. Between 1933 and the outbreak of World War Two, he would go on to write almost 200 articles for a variety of magazines, but mostly for Punch and an aircraft magazine called The Aeroplane. In 1934, his first novel was published by Hamish Hamilton. No Sky, a story about a young Cambridge graduate who obtains a job in the time-and-motion department of an engineering firm, drew on the author’s experiences of working in factories. It received respectable reviews but, according to Balchin, it only sold about 600 copies. Another Balchin title was published a few weeks later. How to Run a Bassoon Factory; or Business Explained appeared under the pseudonym Mark Spade. The reason for this was because, as the author put it, “It wouldn’t have done for me to reveal that I found anything funny about business life.” The book (a satire of business strategy) sold consistently well for a very long time but Balchin was not unveiled as the author until as late as 1950.

In 1935, Nigel left the N.I.I.P. and was taken onto the staff of Rowntree’s, being made assistant to the Chairman. Between 1934 and 1936 he wrote two more novels and three non-fiction books. The first of the non-fiction books, Business for Pleasure, was a sequel to How to Run a Bassoon Factory. The second, Fun and Games; How to Win at Almost Anything, was in the same humorous vein, satirising sport in the same way as the earlier books had satirised business. (Both of these books appeared under the ‘Mark Spade’ alias.) The last in this run of factual books was entitled Income and Outcome and comprised a relatively serious look at the issue of personal finance. The first of Balchin’s novels, Simple Life, was praised by Cyril Connolly and also had the distinction of being banned by Boots Library for being too racy! The second novel, a comedy called Lightbody on Liberty, was rejected by Hamish Hamilton and thus appeared under a new imprint, that of William Collins.

In the mid-1930s, Nigel branched out by writing plays. Some of these remained unperformed and others (such as Power in 1935 and Peace in Our Time in 1936) only made it as far as Croydon Repertory Theatre. A few did reach the West End, one of which, Miserable Sinners in 1937, was written by Balchin as a vehicle for James Mason, his old college friend. Another, Profit and Loss, was performed a year later. Also in the mid-1930s, Balchin began broadcasting on the radio. This association would last throughout the rest of his life: Nigel was in great demand in the late 1940s and early 1950s in particular, when he was often employed by the BBC as a panellist on radio shows such as Any Questions, The Brains Trust and Sporting Questions. In November 1937, Nigel’s second daughter, Penelope, was born. In later life she has become better known as the writer and child psychologist Dr Penelope Leach.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Nigel went to work for the Ministry of Food. This job almost certainly arose from his Rowntree’s connections, because he was put in charge of the allocation of raw materials, dealing mainly with commodities such as sugar and cocoa. Originally he was based in London but in June 1940, when the Ministry was evacuated to Colwyn Bay, the Balchin family relocated to North Wales. After about two years, Balchin left the Ministry of Food and joined the Army, being attached to the Directorate of Selection of Personnel at the War Office. In essence, Nigel’s job involved assigning new recruits to jobs in the Army for which they would be best suited. Vast numbers of men (about 15 000 a fortnight) were turning up at recruiting centres at this point in the war and a method had to be found for keeping tabs on them all. Nigel had the revolutionary idea of putting information about the recruits onto punched cards and automating the assignment procedure. Apparently, within a fortnight of arriving at the training centre to which he was assigned, the commandant was asking Nigel for advice on how the unit should be run. It is clear that Nigel was a great success in his first job in the Army.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Nigel went to work for the Ministry of Food. This job almost certainly arose from his Rowntree’s connections, because he was put in charge of the allocation of raw materials, dealing mainly with commodities such as sugar and cocoa. Originally he was based in London but in June 1940, when the Ministry was evacuated to Colwyn Bay, the Balchin family relocated to North Wales. After about two years, Balchin left the Ministry of Food and joined the Army, being attached to the Directorate of Selection of Personnel at the War Office. In essence, Nigel’s job involved assigning new recruits to jobs in the Army for which they would be best suited. Vast numbers of men (about 15 000 a fortnight) were turning up at recruiting centres at this point in the war and a method had to be found for keeping tabs on them all. Nigel had the revolutionary idea of putting information about the recruits onto punched cards and automating the assignment procedure. Apparently, within a fortnight of arriving at the training centre to which he was assigned, the commandant was asking Nigel for advice on how the unit should be run. It is clear that Nigel was a great success in his first job in the Army.

Before he took up his next Army posting, Balchin’s fourth novel appeared. Darkness Falls From the Air was published in November 1942. The war seemed to energise Balchin’s writing, as this novel far surpassed its predecessors. It was set in London during the Blitz. The hero is an idealistic temporary civil servant who finds himself constantly at loggerheads with his superiors (the book was undoubtedly inspired by Balchin’s spell with the Ministry of Food). Darkness Falls From the Air is a great satire of wartime bureaucracy and a poignant, dramatic novel. It is also very funny. The critics were impressed and the book received some highly favourable notices. However, owing to the paper rationing in force at the time, the novel apparently sold only about 5000 copies in its first edition and there was no paper available for a reprint.

Having ameliorated the Army’s personnel selection problems, Nigel was transferred to a newly inaugurated department responsible for scientific research, becoming Assistant Director of Biological Research. Here he investigated such aspects as how to obtain information from battle fronts using questionnaires and performed time-and-motion studies of gun drills. Balchin’s first contact with the scientific wing of the Army was to provide the inspiration for what remains probably his best-known novel. The Small Back Room was published at the end of 1943. It told the story of Sammy Rice, a weapons research scientist with a false foot and a marked lack of self-confidence, who is asked by the Army to investigate a new type of bomb that is being dropped by the Luftwaffe and has already claimed the lives of a number of people, most of them civilians. The book was another savage satire of British wartime bureaucracy but this time it featured a fantastic dramatic climax in the scene in which Sammy has to deactivate the bomb on a beach, knowing that another example of the device has just killed the Army officer he has been working with on the project. This scene was the highlight of the memorable film made from the book in 1949 by the team of Powell and Pressburger. The Small Back Room received very good reviews and, according to Balchin, “Somehow Collins managed to conjure up a lot of paper” and so the book sold very well. It has been reported that The Small Back Room was the first book bought by General Montgomery on his return to Britain from Africa at the end of 1943.

Three days after the publication of the novel that made his name, Nigel was transferred to another scientific department of the War Office. This posting culminated on 7 May 1945 (the day before VE Day) in his appointment as Deputy Scientific Adviser to the Army Council, a job that carried with it the rank of Brigadier. Among other things, he made a study of psychological warfare whilst employed in this role.

Soon after the end of the war, the Balchin family (with the addition of third daughter Freja, born on Boxing Day 1944) moved to rural Kent. Nigel chose to build on his wartime success as a novelist and to become effectively a full-time writer, although he still retained some business interests, principally as a marketing consultant to Rowntree’s. Through the auspices of its Chairman Seebohm Rowntree, he also resumed his links with the N.I.I.P. He wrote and lectured extensively on the subject of incentives, a matter that was of national importance in the immediate aftermath of World War Two. As well as suggesting ways in which post-war production could be increased, Balchin, a compassionate and humanitarian individual, was still striving to improve the lot of the ordinary worker, just as he had done at the start of his working life.

In September 1945, Nigel’s next novel, Mine Own Executioner, was published, to almost universally rapturous reviews. This book was a gripping tale of a psycho-analyst who agrees to treat a young R.A.F. pilot with schizophrenia and then realizes too late that he is out of his depth. Once again, the book sold in large quantities.

At this point in his career, after three novels in three years that had been constructed to a similar pattern, Balchin was perhaps in danger of being typecast. In 1947 he attempted to deal with this perception by writing Lord, I Was Afraid. This experimental book was written in the form of a play and confounded the critics. Anthony Burgess (writing some years later) described it as “an epic dramatic fantasy” and even adapted it for the stage whilst he was at teacher training college. Several other influential critics were impressed but there was also a feeling among the reviewers that Balchin was being too clever and too obscure for his own good. The reception accorded the book was highly ironic: the author had been criticised for writing to a formula and for not wanting to take risks; when he bravely departed from this formula he was accused of turning his back on what he did best. As one critic rather acidly put it: “Mr. Balchin’s dynamic is elbow grease and the sooner he realizes it the better.” Incidentally, among all his novels, Lord, I Was Afraid is the one that Nigel himself valued most highly.

Also in 1947, the novelist turned his hand for the first time to writing film scripts, adapting Howard Spring’s Fame is the Spur for the cinema. In the same year he adapted his own novel Mine Own Executioner. It was a distinct critical success, the News Chronicle stating that Mine Own Executioner was “The fourth notable British post-war film”, the other three being Great Expectations, Brief Encounter and Odd Man Out.

Other film successes followed for Balchin, both as a scriptwriter and as the provider of highly filmable material in the form of his novels. In 1952 he drew plaudits for his script for the Ealing film Mandy, a compassionate piece about a young deaf girl. Perhaps the high point of his scriptwriting career came in 1956 when he was awarded the BAFTA award for ‘Best Screenplay’ for The Man Who Never Was, a true story from the Second World War in which the Navy plant misleading documents on a cadaver that is then allowed to wash up on a beach, in the hope that the information will reach the Nazis and confuse them regarding British military activities.

Back in the world of novel-writing, the summer of 1948 saw the publication of The Borgia Testament, an historical novel written from the point of view of Cesare Borgia. The following year, A Sort of Traitors arrived at the bookshops. This volume, a return to more familiar Balchin territory, concerned a group of biological research scientists who, despite developing a cure for epidemics, find that scientific progress is stymied by a government minister who is convinced that a foreign power could use the work for nefarious purposes. The book was filmed in 1960 by the Boulting Brothers and retitled Suspect. (A much earlier film version by Alexander Korda, in which Richard Attenborough was to have played the lead, had fallen through.) In 1950, Balchin turned his hand again to non-fiction with the publication of The Anatomy of Villainy, a series of historical essays.

A highly significant episode in Nigel Balchin’s personal life occurred in 1948. His wife, Elisabeth, had enjoyed positions of responsibility during the war, particularly when she landed the job of vetting agents for the Special Operations Executive, the cloak-and-dagger outfit that had been invited by Winston Churchill to “Set Europe ablaze”. When the war ended, Nigel expected his wife to enjoy a life of rural domesticity, tending the garden and keeping bees. It was not perhaps one of his greatest ideas: Elisabeth was highly allergic to bee stings…. Realising that his wife was bored and restless in the country, Nigel started to invite home for the weekend certain friends and acquaintances of his that he thought would interest her. One of these was the sculptor and painter Michael Ayrton. Elisabeth was immediately attracted to Ayrton; as Nigel was also quite taken with Ayrton’s partner Joan, all went well for a while. A period of light-hearted ‘wife-swapping’ ensued, with the two couples holidaying together and spending a lot of time in each other’s company. However, Elisabeth and Michael Ayrton then fell in love and, when Joan chose to withdraw from the arrangement, Nigel found himself out in the cold. A harrowing period resulted for him. Much of the anguish and turmoil that Nigel experienced at this time found an outlet in his 1951 novel A Way Through the Wood, which can be read as a fictionalised account of his marital break-up, and perhaps as an attempt to make sense of all that had happened to him in the preceding three years.

Nigel eventually divorced Elisabeth on 30 March 1951 and she married Michael Ayrton the following year. In 1949, Nigel had employed as his secretary a young Yugoslav refugee called Yovanka Tomich. (Yovanka, who is better known these days as Jane Balchin, was one of the guests of honour at the Balchin Family Society Annual Gathering held in Bramley, Surrey in September 2008. The Gathering celebrated the centenary of Nigel Balchin’s birth.) Nigel and Yovanka were married in 1953 and this new relationship evidently had a positive effect on Nigel’s writing, leading to the release of two excellent novels in the mid-1950s: Sundry Creditors, another story revolving around an engineering firm, essentially an updated and greatly improved version of his debut No Sky; and The Fall of the Sparrow,a much more wide-ranging book about the trials and tribulations of a charming but unreliable young man. In between these two novels came Last Recollections of My Uncle Charles, a collection of short stories (many of which had already been published in newspapers and magazines) narrated by the title character, a loveable rogue and ‘smoking room raconteur’, to adopt a suitably Balchinesque phrase.

In autumn 1956 the Balchin family, now augmented by Nigel’s first (and only) son Charles, left Britain. Nigel’s scriptwriting prowess led to his being awarded a lucrative contract with Twentieth Century Fox, which involved scripting three films a year for three years. Owing to the supertax regime in operation in Britain at the time, Nigel chose to live abroad for the next five years or so. When he was not working in Hollywood or elsewhere in the world, he spent most of his time living with the family in Florence. He evidently enjoyed the trappings of success: home video footage from the period reveals a world of leisure and copious foreign travel.

During this time, when he was employed as a scriptwriter, roughly one of his scripts per year made it to the silver screen, which is quite a good ratio. However, Nigel disliked having his work tampered with and some of the scripts that he was least proud of were the ones that the studios gave the green light to, while some of the better ones ended up in the bin. Most of the films that he worked on in Hollywood are not well known these days; however, he did write an early version of the script for the infamous 1963 film Cleopatra starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (at the time, the most expensive movie ever made) but the version that finally hit the screen was a long way removed from the original and Balchin was not mentioned in the credits.

Nigel experienced a marked decline in his health at the start of the 1960s. He had drunk heavily for some time and this may well have led to the haemorrhaged ulcer and associated health problems which caused him to be hospitalised for much of 1961. The family resettled permanently in England the following year, finding a magnificent country house near Rye in Sussex. Nigel’s fourth daughter, Cassandra, was born shortly afterwards. With his health restored, Nigel resumed writing. In 1962, Seen Dimly Before Dawn was published by Collins. It was Balchin’s first novel for seven years (he once said that he did not want to work on film scripts and novels at the same time). Set in the 1920s, this was a warm and slightly nostalgic novel about a schoolboy who goes to stay with his aunt and uncle at their rundown fruit farm and then promptly falls in love with his aunt when he discovers that she is not in fact married to his uncle. Despite Balchin’s long absence from novel-writing, the book was accorded a very good reception by the critics (and it sold well too).

Although two of Nigel’s novels (The Small Back Room and Mine Own Executioner) had previously been adapted for television by his son-in-law John Hopkins, Balchin himself had never written specifically for the smaller screen. This gap in his CV was addressed somewhat during the course of the 1960s. The most successful result of this activity was probably The Hatchet Man, a ‘lifting of the lid on Hollywood’ which arose from Nigel’s experience of the film world and was broadcast by the BBC in 1962. It is perhaps surprising that Balchin, as a skilled and experienced screenwriter, and a novelist with a fine grasp of plot, suspense and dialogue, did not write more for television. However, several of his proposals were rejected by the BBC in the 1960s and another reason why he did not write more for the medium was perhaps because he was tired of having his work interfered with in Hollywood.

Balchin’s fourteenth novel, In the Absence of Mrs Petersen, was published in 1966. It was an enjoyable, albeit modest, political thriller. His next book appeared a year later. Kings of Infinite Space was commissioned by NASA to celebrate ten years of the American space programme and Balchin spent a summer at Cape Kennedy engaged on research. Although a long way from the author’s best, the resultant fiction was an interesting and readable book, and functions as a useful historical document, recording the period during which the ‘space race’ captured the public imagination.

Having relocated to London from Suffolk in 1969, Balchin continued writing and broadcasting: he appeared on the radio occasionally and wrote a play, Better Dead, for ITV but there were to be no more novels. Seeking to provide financial security for his family, he accepted the major task of developing a course on creative writing. He had just returned from a series of meetings in the USA when he suffered a heart attack and was admitted to a London nursing home. He died three days later, on 17 May 1970. He was sixty-one.

Unfortunately, as can happen to some writers, the name of Nigel Balchin faded away after he died. Many of his novels were out of print by the time he passed away and over the years the list has dwindled steadily until today and you are very unlikely to be able to find any Balchin novels at all on the shelves of the average High Street book store. However, there are still flurries of activity from time to time. In 2005, Separate Lies, an adaptation of Balchin’s 1951 novel A Way Through the Wood, became the directorial debut of Oscar-winning screenwriter Julian Fellowes. Fellowes updated the story to the present day and it proved to be an interesting and very watchable film. Despite impressing the critics it was not a great hit at the box office. A documentary about Nigel was broadcast on Radio 4 in April 2008, along with a new adaptation of The Small Back Room.

So what is Nigel Balchin’s legacy? He succeeded as an industrial psychologist, film scriptwriter and novelist, and revealed himself to be a highly gifted planner, thinker and achiever during the Second World War. Some of the chocolates that he helped to market in the 1930s can still be found on the shelves of our supermarkets today. A number of the films he scripted or that were developed from his novels are still worth watching, particularly Mine Own Executioner, The Small Back Room, Mandy and The Man Who Never Was. In terms of his writing, Nigel’s final tally was fifteen novels, six non-fiction books and numerous short stories and magazine articles. His best novels deal with universal concerns and still deserve to be read for their wit, humanity, psychological insight, the gripping, streamlined plots, the beautiful economy of the writing style, the ultra-realistic dialogue and, above all else, for sheer readability and enjoyment. Now, a hundred years on from his birth, Nigel Balchin richly deserves to be rediscovered and restored to his rightful place in the pantheon of British novelists.

With grateful thanks to Derek Collett for his contribution to this page. For further reading, please access ‘Nigel Balchin’ by Derek Collett, Book and Magazine Collector, Issue 301, December 2008. See also Derek’s authoritative website dedicated to the life of Nigel Balchin.